October 2024

I started a fight once, at a dinner party.

I tried to start a fight. No-one took my side so it petered out quite quickly.

It was about obituaries.

I kicked off with something to the tune of: “You’re discussing whether or not Oscar Pistorius might deserve an obituary for his sporting achievements. Why not an obituary of Reeva Steenkamp?”

What was wrong with celebrating ordinary people, I wanted to know, in life and in death?

And for crying out loud, who actually needed obituaries anyway? If the criteria for inclusion in the obituary column was titles, medals and wealth, hadn’t these white guys been lauded enough in life?

What was “new” about an obituary in a “news”paper?

I hope I didn’t use air quotes.

But I do think about that conversation sometimes.

Kehinde Wiley is an artist who started out creating portraits of ordinary people dressed up and painted to look like kings, presidents, military generals or captains of industry of old. Often, the subjects are posed to replicate poses made familiar to us through famous portrait paintings from history.

Here’s the artist’s preferred wording of what he does, taken from his website: “Wiley … engages the signs and visual rhetoric of the heroic, powerful, majestic and the sublime in his representation of urban, Black and Brown men found throughout the world.”

I adore his work. I’m a bit obsessed with him.

At the same time as Kehinde uses long-established conventions of portrait paintings to artificially raise the status of his subjects in a viewer’s eyes, he exposes the artifice of portrait painting conventions.

One aspect of artifice: size. A larger-than-life painting of a person must be hung on a wall. Once it is, we we are forced to look up at the subject, as if they were positioned on a stage or an altar. The portrait literally belittles us. (If the subject is seated on a rearing horse, so much the better.)

Look at the size of this 2005 Wiley work called Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps. It’s neck-craningly big.

Two: trappings. There’s a reason that portrait paintings of powerful men are often cluttered with objects. The fur-trimmed cloak, the gleaming desk, the heirloom ring, the richly-furnished room, the shelves of books, the merchant’s globe all intimidate us.

They’re all there to detail the nature of the subject’s power. Even if we don’t totally get the symbolism or significance of a particular ornament or tapestry, the jist is that this is a big-deal guy viewed in the very centre of his domain.

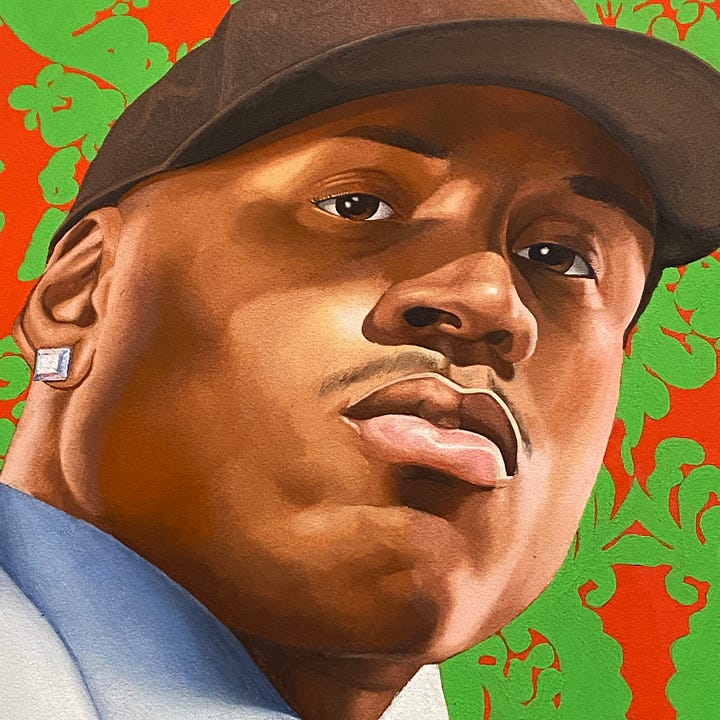

In this painting of LL Cool J, also painted in 2005, notice the hip hop legend’s ring, his designer clothing and his personal crest (created by the artist, with boom box). The painted “wallpaper” behind the subject recalls a previous-century interior bedecked with brocade drapes, silk carpets and expensive wall coverings.

Three: materials and method. In Shakespeare’s time – or before, or after – if you wanted your portrait to be as impressive as possible, you commissioned the best artist. That cost money. If you wanted the portrait – like your legacy – to last, the artist would use the most durable materials available. That cost money too.

Kehinde Wiley does not work with thread on cloth. His paintings are not from or for the domestic realm, and they’re made to last. Wiley does not experiment with expressive painting styles. His brush skill is inimitable. It represents rare talent and years of labour.

In his portraits of Swizz Beatz (Kasseem Dean) and Alicia Keys, Wiley’s celebrity and the celebrity of his music industry subjects reinforce each other.

Keys and her husband honour Wiley with their patronage; he honours them with his conventional/subversive style. Their association as successful Black artists is cemented by these works.

In some ways Kehinde’s recent relationships with patrons is old-fashioned.

What makes these relationships unique is that his career began with exposing the artifice of conventional portrait painting.

Anyone who commissions a portrait by Wiley knows his purpose. Wiley paints portraits of people who are not white men. He magnifies the power of his subjects using the conventions created by white male subjects and white male painters in history.

We were in the Presidents Hall at the National Portrait Gallery the other day. It’s a good place to take visitors. All the official portraits of every one of the presidents is hung there, in order.

The captions are excellent. For instance, Lyndon B Johnson thought his own official portrait was “the ugliest thing I’ve ever seen”.

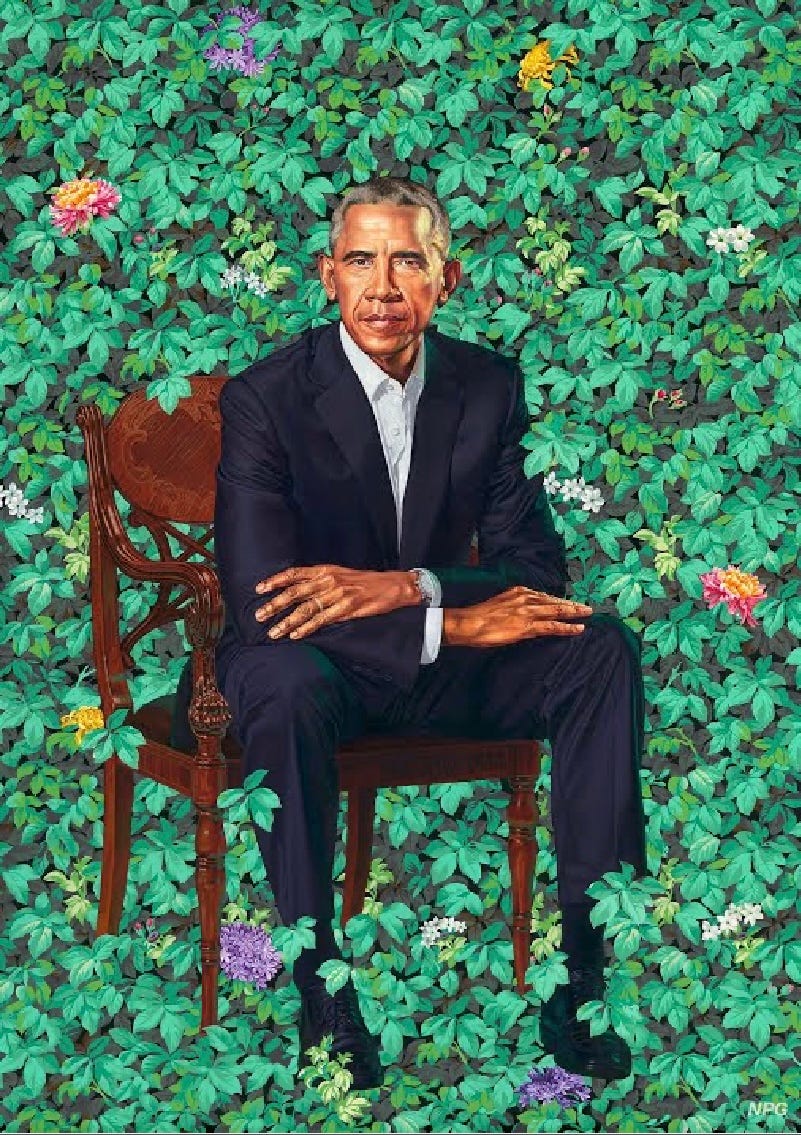

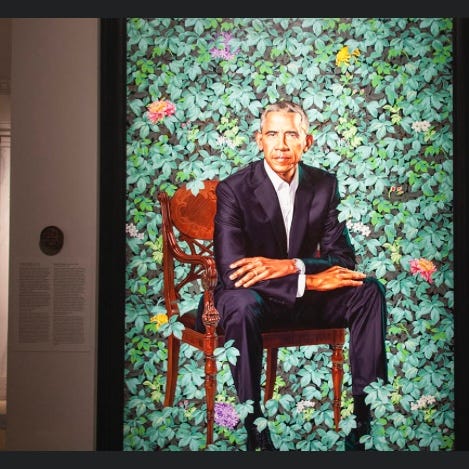

Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama, America’s 44th president, is centrally positioned.

It’s a grand painting – big, beautifully executed – and it’s flattering. In terms of conventions related to memorializing powerful men, that’s three boxes ticked: imposing, naturalistic and technically impressive.

Visitors often make a beeline for the Obama portrait. It seems to be lit from behind, making the Easter egg colours of the background flowers unapologetically bright.

I mean this literally. The painting is oil on canvas but it does seem to glow. The frame has a flat screen TV look about it, if you position yourself at 90 degrees to the painting, so maybe I’m right.

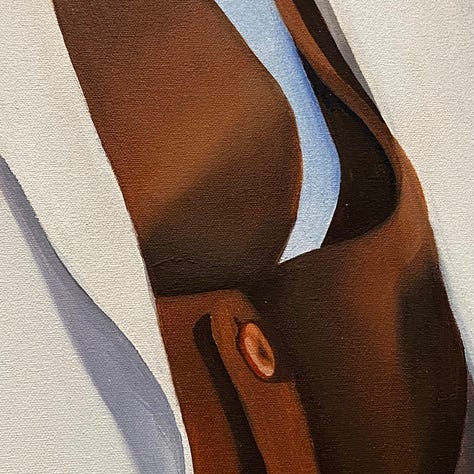

Crowds gather in front of Kehinde’s painting. There’s space to lean forward to admire the beauty of Obama’s painted hand, and to step back to see him sitting amongst tropical blooms.

Let’s talk about the flowers. Do they break convention? They do and they don’t.

Traditionally, men who tread the corridors of power are painted indoors. Light from a window may hit one side of the subject’s face.

What’s interesting about Wiley’s oversized blooms is that – even though the leaves and flowers look, at a glance, like a creeper on a wall – their scale and repetitive arrangement across the surface of the painting create a floral design that reads more like wallpaper than a garden.

Also, the former president is wearing a suit. The light on him is not sunlight. We can see that. So we know the flowers are symbolic.

Wiley tells us that the chrysanthemums “reference the official flower of Chicago. The jasmine evokes Hawaii, where (Obama) spent the majority of his childhood, and the African blue lilies stand in for his late Kenyan father.”

I like the way some of the leaves touch Obama and his chair, like fingertips.

An Old Master wouldn’t paint anything living tickling his subject.

Wiley’s engagement with the grand tradition of European portrait painting is complicated. It’s a push and pull. As he says, he finds himself simultaneously “drawn towards that flame and wanting to blow it out”.