May 2025

We’re in the National Gallery here in Washington DC. The artworks here are Very Important Pieces.

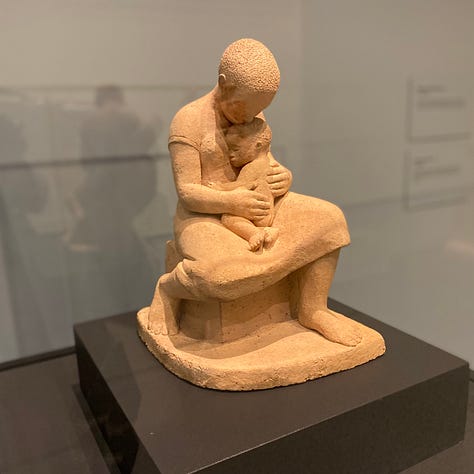

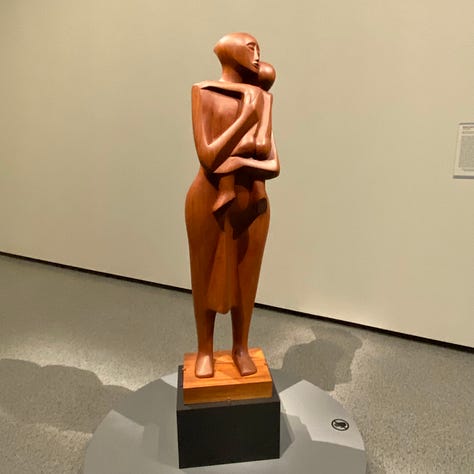

Here’s a smallish sculpture of a barefoot mum with her sleeping baby. It’s less than a foot high.

It’s a very ordinary scene. The mother and child could be inside the home, in front of a fire or in a bedroom. It could be night or day, after the baby’s bath or after lunch. It could easily be the middle of the night, or dawn. It could be outside. Maybe there are people around, maybe there’s noise. Maybe that baby is unwell.

The mother’s bare feet tell me she’s at home. Her pose, her lack of adornment and her simple dress, tell me she’s not dressed to go out.

There’s nothing surprising here. There are women all over the world, right now, holding sleeping babies on their laps.

But have you ever seen an artwork show this moment of domestic peace so well? Not just so well, but so profoundly?

It’s a lot to do with the position of the bodies. The mother’s body forms a protective shell around the child. The baby’s position between her breasts suggests she may have been feeding. The baby is naked, but doesn’t appear vulnerable. In a position that echoes pregnancy, the baby looks nestled.

The fact of the mother and baby’s heads touching draws attention to a connection beyond the physical. There is peace here, but it looks like that peace was earned.

The position of her head tells us that this mother thinks about her baby. The way he’s cradled tells us she feels for her baby.

The mother’s hands and feet are strong and bare. She works to look after her baby.

The position of her legs and feet make her look strongly protective. She looks as if she could pounce, or run, or leap to protect her child.

The baby, in turn, is plump and utterly relaxed. The baby’s calmness and physical wellbeing tell us that this mother is excelling in every way.

If I hadn’t had babies myself, I would have no concept of what it takes – physically, mentally and emotionally – to raise a child.

To be honest, I wouldn’t really care.

I wouldn’t find it particularly interesting that women make and grow humans inside their own bodies. (Until I got pregnant, I was pretty pleased with myself for hair and nail growth.)

I wouldn’t be amazed that they birth babies – it’s really not dissimilar to being hit by a car – and immediately start feeding babies with their own bodies.

I wouldn’t be impressed with women getting up every few hours in the night, sometimes for years at a stretch, to feed and comfort crying babies.

Motherhood wouldn’t seem like a big deal to me. I’d pulled all-nighters writing student essays.

The wilful ignorance around mothering – especially of the mothering of babies, especially by poor or single or hurting mothers – is staggering.

But here it is, a humble sculpture, of humble size, in the humble material of terracotta, encapsulating the miracle of sacrifice that is mothering a baby.

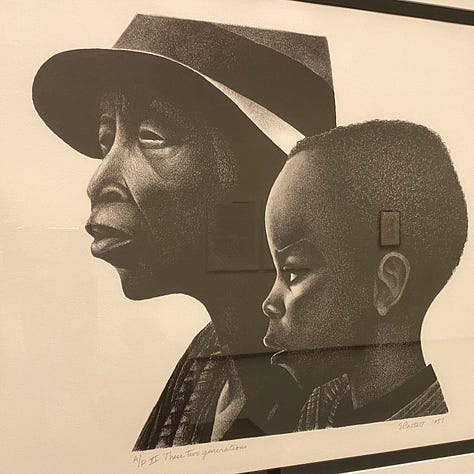

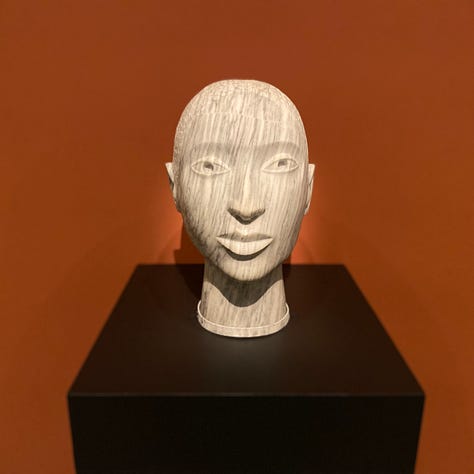

The artist’s name is Elizabeth Catlett. She finished this work, entitled ‘Mother and Child’, in 1952.

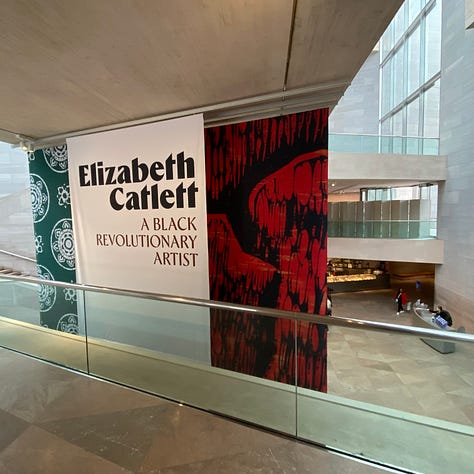

Catlett is currently the subject of a major, multi-roomed retrospective entitled: ‘Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist’.

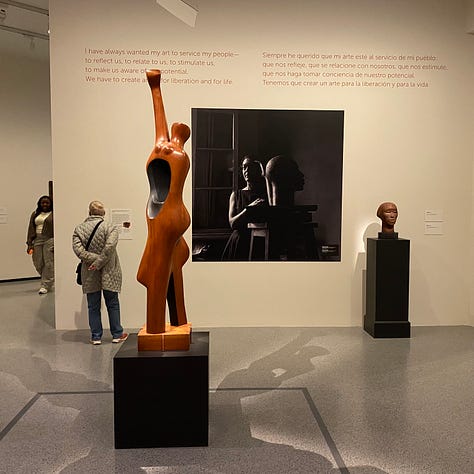

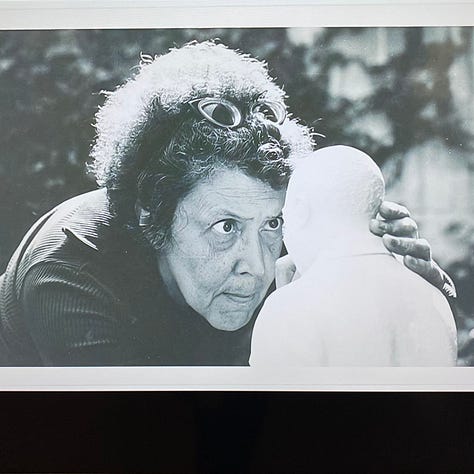

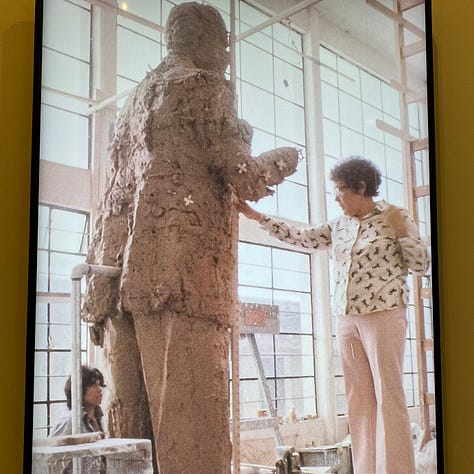

To say that Catlett was a major American artist would be an understatement. In her career she produced perception-shifting sculptures of many media, ranging in size from giant public art pieces to smaller works like Mother and Child.

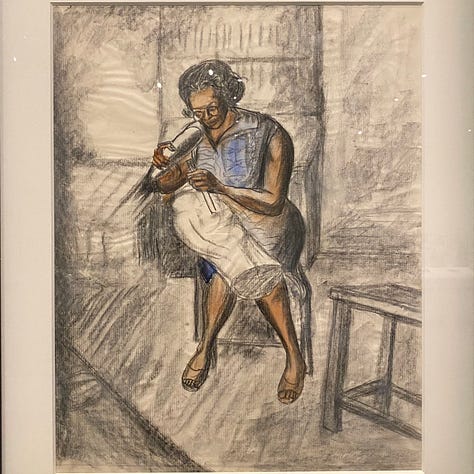

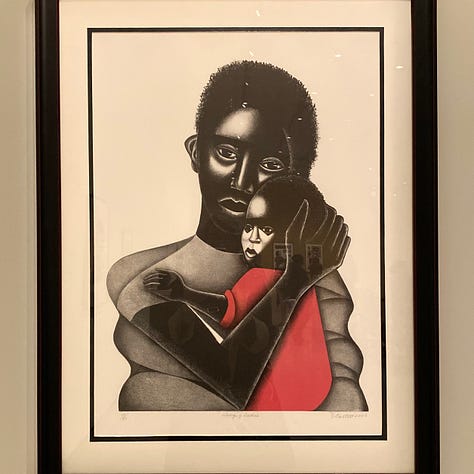

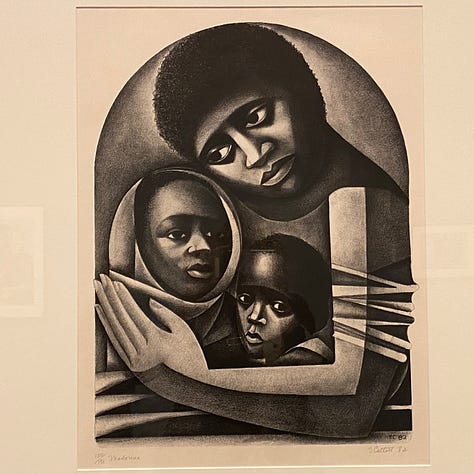

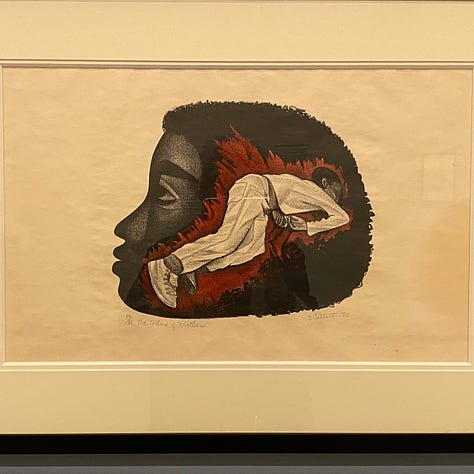

She was astonishingly prolific. Catlett was an accomplished printmaker. She made linocuts and lithographs, woodcuts and screenprints, in black and white and in colour.

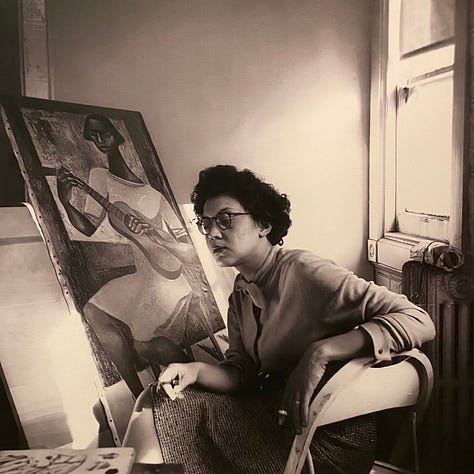

She was a committed activist, who worked within a socialist framework. She lived in Mexico from 1946 until 1972, when the US government allowed her to re-enter her country.

According to the exhibition notes, during Catlett’s 70-ish year career “she prioritised the subject of Black mothers and children … returning often to the theme in both intimate prints and commanding sculptures.”

When she sculpted ‘Mother and Child’, Catlett was already a mother.

‘Mother and Child’ has a religious feel. The mother is a figure of a gentle stoicism and her bowed head lends the work a spiritual air.

But Catlett’s career-long subject was, primarily. Black women.

“While mother and child depictions are frequent in Western art, representations of Black mothers are far less common” the notes say. “Empowering images of Black mothers, even less so.”

Catlett’s work has been described as generally “fervently anti-colonial and joyfully proud”.

Her subjects are united by the way she portrays them – with purpose and dignity – whether they are world-famous figures like Harriet Tubman and Angela Davis, or whether they are barefoot mums comforting a baby in a dark house in the middle of the night.

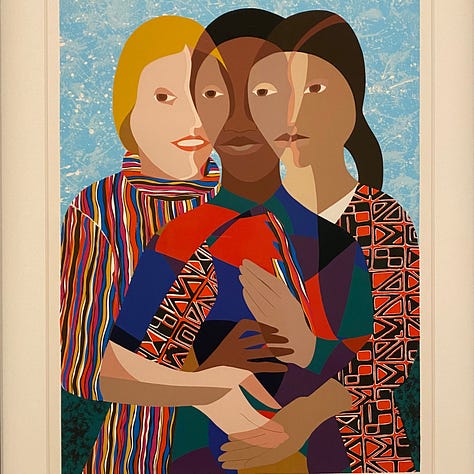

The subject of motherhood served another purpose for Catlett. It was a way of uniting women.

The National Gallery says Catlett used “ideals of the mother-child relationship (and) … women’s shared fear for the health, safety, and well-being of their families. She understood these images as a way of crossing geographic and cultural boundaries to connect women.”

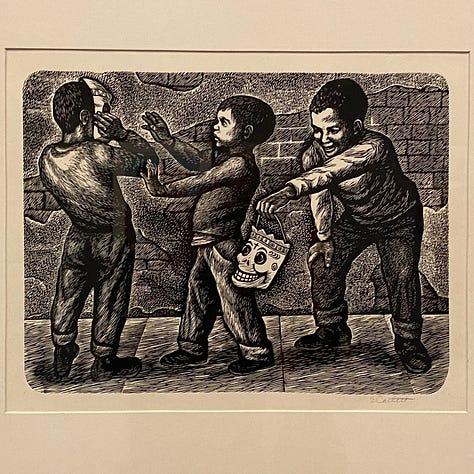

Catlett had three boys: Francisco, Juan and David. That’s them in the linocut Mis Ninos. They are shown celebrating the Day of the Dead.

Catlett was born in 1915 and died in 2012. She was an artist and an activist from high school until her death. But she switched gear when she had young children.

The notes tell us: “From 1947 to the late 1950s Catlett focused on raising her children and turned from making sculptures to prints – a medium more conducive to working from home.

“She returned to sculpting after her youngest son David started kindergarten.”

David worked as his mother’s studio assistant for more than 30 years.

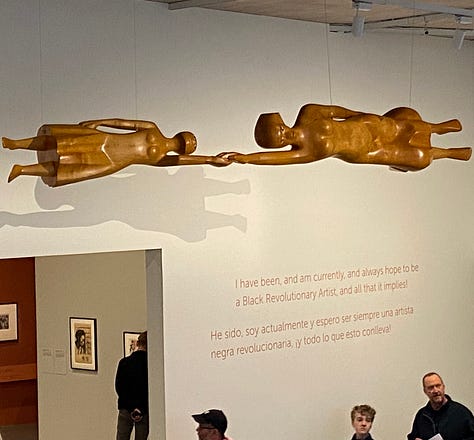

At the end of Catlett’s life, she had arthritis. She designed and made sketches for a sculpture called “El Abrazo” (The Hug).

It was David who sculpted the work, in Guatemalan red mahogany, completing it five years after his mum’s death.

At the age of 83, Catlett completed the sculpture “Naima: My Granddaughter” (1993). Naima, this child of one of her sons, was one of Catlett’s final dignified and purposeful Black woman subjects.

Magnificent (sculpture, artist and story)! Thank you so much for sharing it xx

I really love this piece and your attention to the role of mothers. Well done! And Happy Mother's Day (every day!)!